The standard of care that Surrey residents should be getting seems out of reach now and in the near future despite NDP's plan to invest $1.7 billion to build a new hospital

Home to over 600,000 people, Surrey is one of the fastest-growing cities in the Lower Mainland, with its population increasing by almost 10 percent every year. Compared to other cities, Surrey is far more welcoming due to its affordability, diversity and economic opportunities, which makes it a hub for the immigrant population. Given this and the federal mandate to bring more workers into the country, Surrey is projected to become the most populous city in BC in the next two decades. However, this growth has strained the city's healthcare system, leaving hospitals under-equipped to take care of its increasing population, a vital issue that needs to be addressed.

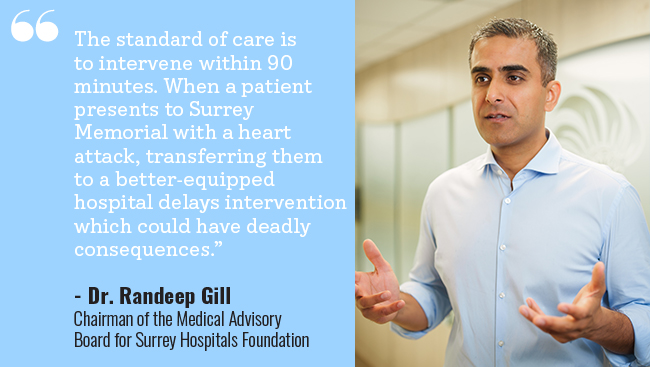

As Surrey residents and the medical community reel under pressure to somehow manage its hospital needs, politicians and political parties play the blame game and offer solutions that are inadequate for the community's growing needs. Dr. Randeep Gill, chairman of the Medical Advisory Board for Surrey Hospitals Foundation, shares his firsthand experience from the ER at Surrey Memorial Hospital, providing insights on what the city needs versus what it's getting when it comes to an issue that directly impacts its residents' survivability.

Hospital Crisis in Surrey

Surrey Memorial Hospital, recognized as a regional hospital, provides specialized care to the ever-increasing population of Surrey and surrounding areas. The hospital's Emergency Department is the busiest in the province and second busiest in the country and took care of a staggering 171,467 Surrey residents in 2022-23. On average, the hospital sees close to 600 patients a day. As it grapples with this overwhelming patient volume, the hospital struggles not just with the problems of overcrowding and understaffing, which is the bane of the healthcare sector in the current times, but also a lack of infrastructure when it comes to specialized care. As a result, close to 1400 critically-ill patients had to be transferred to other hospitals north of the Fraser River for life-saving interventions in 2021 alone.

In February this year, the Surrey Board of Trade released a report titled "Surrey's Hospital Needs," highlighting the lack of hospital infrastructure in Surrey. The report underscored that Surrey is the only large city in Canada that lacks the necessary facilities to treat three leading causes of death: heart attacks, strokes, and trauma.

Dr. Gill, who has been advocating for a change in the situation, understands that Surrey residents deserve more and that the government is not adhering to the standard of care south of the Fraser. "Surrey is the second largest city in BC with a high incidence of heart attack, stroke, and trauma—so, why is there no plan to bring life-saving resources to the community?" he asks.

According to Gill, every major city in Canada has a hub for addressing the leading causes of death. However, despite being situated in one of the largest and fastest-growing cities in the country, Surrey Memorial Hospital does not have the necessary infrastructure to intervene when it comes to these causes of death. The hospital's cardiac department can manage heart failure or deal with patients with heart infections, but it's not equipped to perform surgeries like valve replacement or vessel opening. Gill states, "The standard of care is to intervene within 90 minutes. When a patient presents to Surrey Memorial with a heart attack, transferring them to a better-equipped hospital delays intervention which could have deadly consequences."

Dr. Courtney Young, Head of the Cardiology Department at Surrey Memorial Hospital, agrees with Gill and has been pushing for a catheterization (cath) lab to cater to the needs of Surrey's growing population, which is more prone to heart attacks. "Surrey's population is unique from the rest of the lower mainland as it consists of people of South Asian descent who are genetically predisposed to a higher prevalence of heart attack," she says. Currently, most patients presenting with a heart attack are taken to Royal Columbian Hospital, while 30% still go to Vancouver General Hospital or St. Paul's, depending on where they can be accommodated. "Part of the way to treat a heart attack is to take these patients to a cath lab. However, despite such a high incidence of heart attack in this demographic and knowing that time is of the essence, we still don't have a cath lab yet," she adds.

The situation is equally grim when it comes to the hospital's pediatric department, which has 12 pediatric emergency rooms. It was built to serve 20,000 patients a year but saw over 51,000 patients in 2022. What's worse is that the hospital does not have a pediatric ICU. "Lack of pediatric specialty care was among the top three reasons why close to 1,400 critically ill patients were transferred to hospitals north of Fraser in 2021," confirms Gill.

Another area where the hospital struggles are its maternity services. The hospital's birthing unit was built for 4,000 deliveries a year, but the number of births in Surrey was upwards of 6,000. Five out of seven days a week, the hospital is on diversion, which means that mothers in labour are redirected or left at the mercy of other hospitals, such as Peace Arch which is often on diversion itself. "My wife, who is an anesthetist and on call for Peace Arch regularly, is witness to the number of times both the hospitals are on diversion, yet there is no plan to increase the capacity. Despite knowing that Surrey is a growing community with many young families, we have only added four new maternity beds at the Surrey Memorial Hospital in the last two decades. How does any of this make sense, and how are we taking care of the community and the new immigrants we are bringing into our country?" asks Gill.

New Surrey Hospital

To tackle the hospital crisis, the NDP government is investing $1.7 billion to build a new hospital in Cloverdale. Lauding this development as an "extraordinary moment" for Surrey, Health Minister Adrian Dix said, "We have 18 major hospital projects in BC, but out of these, only one is a new hospital, only one community has that priority, which is a fundamental change in approach from the previous government."

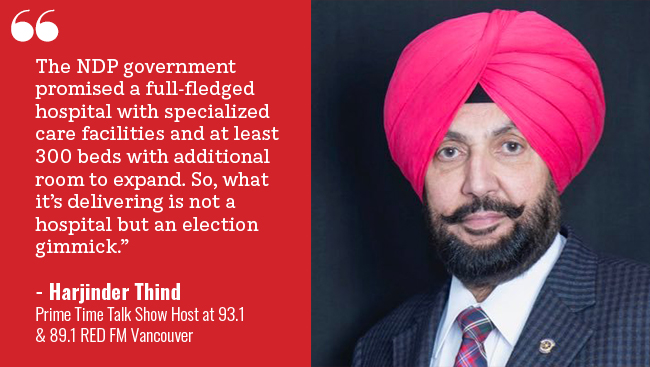

Though it may sound promising, the reality is quite different. The new hospital will only increase the region's diagnostic and primary care capacity while offering 168 acute care beds, an ER, and a cancer center. All evidence suggests that this is not enough to address the needs of the province's fastest-growing community—one that is already behind other Canadian cities when it comes to specialized care. Surrey residents, community leaders and medical professionals feel betrayed by what the government is finally implementing after a six-year wait. Harjinder Thind from Red FM, who has been closely monitoring the developments and advocating for a new hospital for almost two decades, says: "The NDP government promised a full-fledged hospital with specialized care facilities and at least 300 beds with additional room to expand. So, what it's delivering is not a hospital but an election gimmick."

Referring to the new hospital as a "glorified urgent care center," Kevin Falcon, leader of the opposition, said that it's absolutely inadequate for Surrey's exploding population and that calling it a hospital is a bit of a stretch. "A hospital without a maternity ward for the youngest population in BC is unacceptable," he added. Expressing his dissatisfaction with the location, he remarked, "It shows a lack of vision from the government as Cloverdale is not ready for a hospital. The government will need to invest further to make it feasible to run a hospital there, which can take years."

Commenting on the location, Minister Dix said, "We had a much better hospital site on the Corner of 152 and Highway 10, which the previous government already sold." Elaborating further, he said that Cloverdale is not just one of the fastest growing areas of Surrey, but will be one of the fastest growing areas of BC. It has the further advantage of being connected to Kwantlen Polytechnic University, and proximity to post-secondary education is essential for a hospital site.

When questioned about the absence of infrastructure in the new hospital for the three leading causes of death or the lack of plans for a maternity ward, Minister Adrian Dix responded that his government is trying to make up for the BC Liberal Party's failure to invest in Surrey's healthcare and the new hospital is a "dramatic improvement" from what the previous government did for the community.

Downplaying the need for specialized care in Surrey, Minister Dix stated, "80% of patients at Surrey Memorial Hospital do not need critical or specialized care." He suggested that the new hospital aims to alleviate Surrey Memorial Hospital's burden of non-specialized services, implying that the current infrastructure at Surrey Memorial Hospital is satisfactory for meeting the region's healthcare needs as long as the new hospital can cater to non-critical patients.

Dr. Sujatha Nilavar, a family physician residing in Surrey, said that the government's failure to provide resources within the community amounts to neglecting the community's requirements. She adds that redirecting women in labour to nearby hospitals or transporting critically ill patients by ambulance north of the Fraser River falls below the standard of care they aim to provide for their patients.

As a medical voice in the community, Gill looks at the new hospital as a community hospital that will not advance care the way it should. "The stakeholders—Ministry of Health, Ministry of Finance and Fraser Health Authority need to be transparent about their decision-making and what impact they hope to achieve by pumping $1.7 billion into this new hospital," says Gill.

Fraser Health Authority's primary mandate is to receive funding from the government and manage patients within its region. They collect data on community needs and have the power to advocate for better, more robust infrastructure. When contacted to understand why they supported the new Cloverdale hospital, they declined to respond directly and deferred the request to the Ministry of Health.

Meanwhile, Gill remains unconvinced of this new hospital in its current form. "I see no strategic advantage of having a community hospital in Cloverdale. Although a new hospital is welcomed, it doesn't address the growing needs of our community," he says. He suggests that one of the ways the government can bring new infrastructure to Surrey is by building a new critical care tower directly on the Surrey Memorial Hospital campus. Gill elaborated that "building a second critical care tower and tying into the existing infrastructure was originally planned for 2013-14. Doing it now would allow Fraser Health the expanded footprint to add acute care services such as Interventional Radiology, Cath Lab, Dialysis, expand our OB and Pediatric departments, finally addressing the community's needs."

On the other hand, Anita Huberman, President of the Surrey Board of Trade, sees this new hospital as an opportunity to support a thriving community in a new area. "The BC government has engaged in Surrey, but we're still playing catch up. We all need to sit down with the Minister and look at priorities," Huberman says.

Fraser Divide: North Vs. South

As Surrey accelerates towards becoming the largest city in BC, successive governments continue to underestimate its needs and follow their traditional investment patterns. Surrey has historically received less healthcare investment than Vancouver, with Fraser Health Authority receiving $2,229 per capita compared to Vancouver Coastal Health receiving $3,033 per capita. Extrapolating over 600k people in each city translates to a difference of $500 million annually. "We have universal health care funded equally by taxpayers throughout the province. So, it's beyond me why one area of BC should get more funding and infrastructure than an area that's rapidly growing," remarks Gill.

In alignment with the government's funding priorities, St. Paul's Hospital in Vancouver is getting a new replacement building spread across 18 acres just east of Vancouver's downtown core. The 1.2 million square foot acute care hospital will be attached to a world-class research hub with a multitude of high-end, state-of-the-art, life-saving interventions despite its proximity to Vancouver General Hospital.

Many residents wonder why Surrey won't be receiving such a facility, despite the provincial government's assurances that it truly prioritizes the city. Residents such as Dr. Arvinder Bubber, FCPA, FCA and Former Chancellor of KPU are not surprised. "Traditionally, Vancouver has exerted a lot of political weight, which is why governments have always invested in such facilities there," he shares. Harjinder Thind shares his frustration, juxtaposing Vancouver, which has five major hospitals, with Surrey, which is somehow managing with only one despite a massive influx of people settling there. "We have close to 1,500 new people coming to Surrey every month, and soon we'll surpass Vancouver in terms of population, yet we're unable to get a brand new, full-fledged hospital," he says.

Harjinder Thind explains that Surrey Memorial Hospital was built for 350,000 people and was saturated long ago. "If you visit the hospital, you'll find dozens of patients in the hallway screaming in pain while there's no one to take care of them because the ratio of patients to the medical staff is grossly uneven, with most of them feeling completely burnt out, which is why we need a brand new, modern hospital with state-of-the-art facilities," he says.

Even within the Fraser Health Authority, there's a lot of disparity in the funding and infrastructure between hospitals on the north and south of the Fraser River. For instance, the maternity beds in Surrey have increased by four from 28 to 32 over the last two decades. Surrey Memorial Hospital's Birthing Unit is at capacity and sometimes on diversion five out of seven days a week. Yet, there is no approved or funded plan to expand the number of maternity beds in Surrey. Meanwhile, maternity expansion is scheduled for the Royal Columbian Hospital in New Westminster for 2025, increasing the maternity bed count from 24 to 48, making it the largest maternity centre outside BC Women's Hospital. That hospital is also getting a new cath lab to open in 2025.

According to Gill, such a discrepancy continues because the government is following old patterns, where funding followed the perceived base of power. "If you don't question the government, you won't get your fair share. It's time our community comes together, voices their opinion and advocates for change. Earlier, the political base was concentrated in Vancouver, but that has changed. Earlier, there were no political ramifications if governments didn't pay attention to the residents of Surrey because the voter base wasn't there. But now the road to the Premier's office goes through Surrey, and if we speak up and talk about our needs, the funding model will soon reflect that," says Gill.

Dr. Arvinder Bubber is also hopeful that things will get better for Surrey in the future. "We need to have a transparent and robust conversation with the government. I'm also excited about the SFU medical school being set up in the city, as that means more doctors will be part of the fabric of Surrey. We have traditionally lacked training hospitals in Surrey, and a medical school will be a great boost for the Surrey healthcare system," he says.

Conclusion

Surrey's rapid growth has strained the city's healthcare system leaving hospitals under-equipped to care for the community's needs. However, what has made matters worse is the lack of vision on the part of the government to bring in more specialized infrastructure to adequately handle the patient volume. It is apparent that the traditional model of redirecting these treatments to hospitals north of Fraser is no longer just or equitable. As well, the Fraser Health Authority should take accountability for its mandate and assert its power on behalf of the people of Surrey.

After talking to the community, it is apparent that they unanimously want an upgrade from the existing hospital infrastructure that will serve the community's needs today and continue to accommodate imminent population growth. People also seemed tired of the government politicizing and playing the blame game on such a critical issue that directly impacts survivability. Regardless of what the previous governments have done, coming through for the community now is essential—and to do that, the government, medical professionals and community leaders must be aligned on a solution that takes care of the people of Surrey today and tomorrow.