Every April, communities across Canada unite to raise awareness about the life-saving impact of organ and tissue donation, with National Organ and Tissue Donation Awareness Month at its core. It’s a time to spark vital conversations with loved ones about the lasting impact of donation. Fittingly, April also marks Sikh Heritage Month, offering a timely opportunity to explore the cultural and spiritual connections between Sikh values and the act of giving life.

Dr. Reetinder Kaur, project director at the University of British Columbia’s Kidney Transplant Research Program and Punjabi Language Instructor at Simon Fraser University, leads organ donation advocacy efforts and has spent over five years working closely with transplant patients, donors, and families. As a newcomer to Canada in 2020, Dr. Kaur immediately noticed a critical gap. “What struck me most was that the storytelling around organ donation and kidney transplantation lacked representation from the South Asian community, specifically the Punjabi-speaking Sikh community,” she shares.

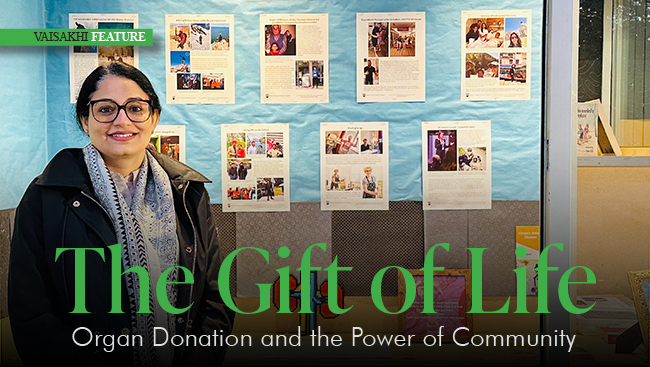

Dr. Kaur’s fluency in Punjabi, combined with her understanding of cultural and religious nuances, positioned her to fill this gap. Through community engagement and research, she’s helped give voice to stories that often go unheard. One such initiative is her powerful multilingual photo exhibit, Surviving and Thriving, which highlights stories of Punjabi living kidney donors and transplant recipients.

Among the stories featured in the exhibit are that of Randeep Singh and Mantej Dhillon. Randeep, diagnosed with kidney failure, made a public plea for a living donor on Punjabi radio. A complete stranger, Mantej, heard his story, got tested, and turned out to be a match. His selfless act not only saved a life but inspired an entire community. “Their story is the embodiment of seva,” says Dr. Kaur, referring to the Sikh principle of selfless service.

For many, like Gurjit Pawar, a Registered Nurse who works with patients living with kidney disease and is herself a two-time kidney transplant recipient, the journey is long, personal, and emotionally layered. Diagnosed with kidney disease at just 13 years old, Pawar’s life trajectory changed overnight. “I remember sitting at home with my family when the pediatrician called. My mom answered the call and looked at me with fear in her eyes. That phone call changed everything,” she recalls.

Over the years, Pawar endured various treatments, including dialysis. Her diagnosis not only altered the course of her own life but also deeply impacted her mother, who was soon diagnosed with depression, leading to a profound shift in their family dynamics. Pawar details, “This was our first exposure to chronic illness in our family. I don’t think that any of us were given the tools to navigate through it.”

Her first transplant came through a paired exchange program, which is a network that allows incompatible donor-recipient pairs to swap matches with others. Her then-boyfriend, now husband, donated his kidney to a stranger so she could receive one in return. “He stole my heart, and I stole his kidney,” Pawar jokes. Today, they have two sons, the second born via surrogacy due to changes in her health. Pawar’s second transplant came years later, after battling COVID-19 and seeing her kidney function decline. This time, it was a friend—a former colleague—who stepped forward. Pawar expresses, “It’s a hard gift to accept and can be overwhelming to think that this level of kindness exists, but I will forever be grateful to my donors and the community of people that have supported me through this journey.”

From her position in healthcare, Pawar regularly sees the cultural and emotional barriers that persist in the South Asian community. “Organ donation is rarely discussed. We don’t talk about death,” she says. “For those needing a transplant, there’s often guilt, shame, and fear of judgment. It’s not that our culture is negative, but that many people shield themselves from asking for help, or simply don’t have the tools to do so.”

Dr. Kaur echoes the sentiment, adding that women face added cultural pressures. “Some families worry that donating a kidney will affect a woman’s marriage prospects or ability to have children. These concerns add complexity,” she explains. Both stress the importance of education, open conversation, and language-accessible resources. For those unsure where to begin, Dr. Kaur suggests starting with BC Transplant’s website to learn about donation types, eligibility, and the family’s role in consent.

BC Transplant emphasizes that organ donation is the ultimate act of selflessness and generosity. As per BC Transplant, “Living donors who choose to undergo surgery to save someone’s life, and the deceased donors and their families who make this selfless decision during their grief, are profoundly inspiring. We know that 90 percent of British Columbians support organ donation, yet fewer than one in three have registered their decision on deceased donation.”

Undoubtedly, sharing stories is key to breaking the stigma and inspiring action. “If you’re considering donating, talk to someone with lived experience. That had the biggest impact on me,” says Pawar. “I get to live a full life, give back, and raise two beautiful kids. That’s the gift of organ donation.” As April reminds us, giving life is one of the most powerful acts of humanity. In the Sikh community and beyond, it’s a time to reflect, register, and start conversations—because sometimes, a simple dialogue can give someone else a future!