WASHINGTON — Recovery of feeling can gradually improve for years after a hand transplant, suggests a small study that points to changes in the brain, not just the new hand, as a reason.

Research presented Sunday at a meeting of the Society for Neuroscience sheds light on how the brain processes the sense of touch, and adapts when it goes awry. The work could offer clues to rehabilitation after stroke, brain injury, maybe one day even spinal cord injury.

"It holds open the hope that we may be able to facilitate that recovery process," said Dr. Scott Frey, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Missouri in Columbia.

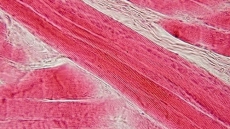

When surgeons attach a new hand, nerves from the stump must regenerate into the transplanted limb to begin restoring different sensations, hot or cold, soft or hard, pressure or pain. While patients can move a new hand fairly soon, how quickly they regain feeling and what sensations they experience vary widely.

After all, the sense of touch isn't just about stimulating nerves in the skin. Those nerves fire signals to a specific brain region to decipher what you're touching and how to react. Lose a limb and the brain quickly rewires, giving those neurons new jobs. Frey's work shows the area that once operated a right hand can start giving the left hand a boost.

Brain scans suggest those changes are at least partially reversible if someone gets a hand transplant years later. But little is known about how the brain's reorganization affects recovery.

Telling where on the palms or fingers they're being touched without looking is a persistent problem for hand transplant recipients, and a function of the brain's main sensory area. Frey's team compared four transplant recipients, four patients whose own hands were reattached immediately after injury, and 14 uninjured people.

The longer the time since their surgeries, the more accurately patients located a light touch, Frey reported. Two who've had transplanted hands for eight and 10 years, respectively, were almost as accurate as uninjured people. So were two patients whose own hands were reattached 1 1/2 and three years earlier.

Nerve regeneration is thought to take about two years, Frey said.

"Yet their sensory abilities and motor abilities continue to improve, albeit gradually, as long as we've been measuring," he said, suggesting the brain continues to adapt.

Hand transplants are relatively new and rare. The United Network for Organ Sharing last summer began regulating them like it does organ transplants, and knows of about two dozen recipients in the U.S. since 1999.

But they offer a model for the brain's ability to reorganize after a stroke or other injuries that are harder to study, said Dr. Gordon Shepherd, a Yale University neuroscientist who wasn't involved in the work.

"It has quite broad implications" for research on recovery, he said.

Touch isn't just a functional sense: Another study presented Sunday examined its emotional side.

Certain nerves register pain or itching. A completely different nerve detects the pleasure of a caress.

Those nerve fibers have been studied mostly in animals. They're found on the backs of mice, less on the limbs and never the paws. In humans, they've been found only in hairy skin. Previously, researchers measured the nerves' activity in human forearms, and found they fired mostly after a gentle stroke that people called pleasurable but not after a fast pat.

The theory is that these nerves evolved for social bonding. So Dr. Susannah Walker of Liverpool John Moores University tested if people experienced empathy when viewing video clips of different touches.

Observing someone being gently stroked, people rated the touch to be pleasurable on the back and shoulder, but less so the forearm and not the palm, Walker found. A fast pat wasn't deemed pleasurable.

"It shows how our brains actually can vicariously take part in not only our own feelings, but in the feelings of those we see about us," said Yale's Shepherd.

Touch is crucial for infant development, and Walker says a next step is learning if these nerves behave differently in developmental disorders such as autism.